WAXWING WANDERINGS

Waxwing Wanderings is a blog designed to share insights on our interactions with native plants and the wildlife they sustain. Topics will wander from sharing botanical discoveries on a hike to featuring ecological stewards within the community that passionately commit their time to restoring Earth’s green spaces.

Reconciling with Ecological Grief

If you are invested in ecological gardening or restoration, you’re familiar with the feeling of joy—the pleasure of watching native wildflowers bloom where once they were absent, for example, or the thrill of seeing a new bird or bee in your gardens because you’ve created habitat.

You are also, most likely, familiar with sadness. These days, to love the earth is to know grief.

Those of us who care for the earth find ourselves contending with the pain of countless losses. Loss of habitat. Loss of the wildflowers and wild creatures who would otherwise make these natural habitats their home. Loss of humans’ relationship with land and the opportunities that more symbiotic relationships would reveal. Loss of beauty. Loss of outdoor recreational opportunities. Loss of clean air and water for humans and wildlife. Loss of biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. Loss of flora and fauna that we never knew existed, and now never will. The list goes on…

Grief over the degradation of our earth is so widespread, there’s an official term for it: Ecological Grief. We’ll explore what this concept entails below. The intensity of this grief is vast and valid.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the presence of Ecological Grief points us toward its antidote. After all, the depth of our grief is a direct reflection of the depth of our love for the earth. Sustaining that love through close relationship with land can provide a remedy for our sadness.

An ecological joy: finding this native sedge growing from a restoration site at the Horn Farm in York, PA.

What is Ecological Grief?

A 2021 paper published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health broadly defined Ecological Grief as “a natural response to ecological loss, which is supposedly particularly pronounced in people who retain close relationships with the natural environment… but may well be universal.”

More specifically, the authors cite two other researchers who define Ecological Grief as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change”. This loss might also include loss of human ways of life and even “loss of personal identity constructed in relation to the physical environment.”

Ecological Grief also is referred to as “climate anxiety,” “eco-grief,” or “solastalgia.” No matter what you call it, you are probably familiar with how this grief feels in your body and mind.

An ecological joy: building community among earth stewards as part of 2025’s Ecological Restoration Certificate (ERC) program.

An Antidote to Grief: Developing a Relational Ethos with Land

Ecological Grief can feel so “big”—like a huge, nebulous force pushing down on us. If left unaddressed, the weight of this grief can threaten our motivation to continue advocating for and taking action on behalf of our ecosystems.

Sustaining a close relationship with land helps counterbalance Ecological Grief, because it offers grounding in the love that undergirds this relationship—and love is a renewable resource.

Furthermore, when we connect deeply with a specific plot of land, ecological challenges and opportunities come into focus. Through close observation, we identify ways in which we might be of service to the land. Taking concrete action is empowering, as it allows you to experience your own capacity for impact. This helps reduce the sense of overwhelm that can arise when thinking about ecological destruction more broadly. As one Rutgers professor puts it, “Action is the best medicine.”

Below are three strategies for deepening your relationship with land. We teach these strategies in many of our educational offerings.

Sit Spots

A sit spot is a place in nature that you visit regularly to practice observation and connection with the land. As the name implies, the goal is simply to sit in a consistent spot and observe quietly.

Returning to the same spot across different days, times of day, and seasons deepens your relationship with that specific place. It provides opportunities to familiarize yourself with changes in the space over time, from shifts in wildlife behavior to the influence of different weather patterns.

Because of its emphasis on mindfulness, a sit spot practice helps cultivate a sense of calm in an ever-changing world. This effect can be amplified by incorporating meditation into your sit spot ritual.

Nature Journaling

Nature journaling involves creating a tangible record of your observations, questions, and feelings about a specific place in the natural world. As you notice wildlife, plants, weather patterns, and your own internal state, you might record these observations using a combination of written words, drawings, photos, leaf pressings, and so on.

As with sit spots, nature journaling encourages slowing down, getting present, and practicing close observation and mindful reflection. Creating a record of your experience helps ground you in your observations and allows you to reflect on your experiences well into the future.

The 2026 cohort of the Ecological Restoration Certificate (ERC) program engages in a creative writing exercise that facilitates dialogue with land.

Dialogue with the Land

Another way to connect with the land around you is simply to talk with it. That might sound odd, but hear us out! This dialogue can take place in different ways.

You might walk through a landscape while paying close attention to cues about where it’s thriving and how it might be ailing. You might sit in nature, enter a meditative state, ask some questions of the land out loud, and see if any responses arise. You might pull out a journal and write down some questions that you have for the land, then respond to those questions as if the land is speaking through you.

There’s no “right” or “wrong” way to approach this dialogue. The point is simply to foster an ethos of listening to the land—inviting the land to be a participant in the process of its own healing. Considering the land as our partner in restoration empowers us to serve as more mindful earth stewards.

Connecting with land can have a rejuvenating effect that strengthens your resilience as you engage in ecological action. When we show up in service to the earth, we find the motivation to continue moving through our Ecological Grief, rooted in love and the restorative fuel that it provides.

Words Shared by Laura Newcomer, Waxwing’s Community Coordinator.

Virtual Field Trip: An Island within A Bay, Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge

Exploring Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) is a memorable day trip for any birder or plant community enthusiast. This refuge is a 2,285-acre island, just off of Maryland’s eastern shore, nestled in the confluence of Chesapeake Bay and the Chester River. This ecologically vibrant space was historically a hunting ground for indigenous peoples and now is protected as a refuge for the over 240 species of birds that inhabit this diverse island. The refuge is a tapestry of different habitats- brackish tidal marsh, forest, meadow, with interspersed cropland.

Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge, a boardwalk trail amidst brackish tidal marsh.

During this Fall field trip, winged or shining sumac (Rhus copallinum) was the botanical showstopper. In the meadows adjacent to the brackish waters, the hue of deep red filled the landscape. Stopping for a puckering pop of lemony-citrus, the little seeds create a memorable taste sensation. Harvest when rain hasn’t dampened the oils that coat the fine hairs on each seed. Freeze until ready to process or dry the seeds immediately in a low humid environment. Create homemade Middle Eastern-inspired Zaatar seasoning or infuse in vodka for a delightful blushed addition to cocktails.

Winged or shining sumac (Rhus copallinum) massed in meadow

Winged or shining sumac (Rhus copallinum) seed head

Given the warm Fall day, a Variegated fritillary butterfly arrived on the open meadow path warming itself with the sunrays. Other field notes of interest were the species;

Northern seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens)- late blooming source of nectar for pollinators

Northern bayberry (Morella pensylvanica)- scratch-n-sniff leaves and fat-filled berries for migratory birds (and historically bayberry candles!)

Goundsel tree (Baccharis halimifolia)- delightful winter interest seed fluff

Devil’s walkingstick (Aralia spinosa)- peppercorn tasting seeds, with overall structure mimicking elderberry from the distance

and a delightful diversity of oaks and pines.

Variegated Fritillary on meadow path

Devil’s walkingstick (Aralia spinosa)

Final ponderings from this field trip was the historical context of land “ownership” of this island and how colonization has shaped our relation with land. This island wasn’t acquired by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service in its current refuge designation until the mid 1960’s after a boon of development rose in the area and the need for conservation was clear from the community. Formerly the space was acquired by Colonel Joseph Wickes and eventually his heirs. Starting as early as the mid 1600’s the island was utilized as a place to grow tobacco and support other land-intensive agricultural practices such as logging, dairying, raising sheep and horses, growing peaches, pears, and asparagus, and then exporting goods from the family shipyard.

The development of these crops, of course, followed after indigenous peoples stewarded this land for shellfish and other forms of naturally occurring sustenance populations, living alongside the migratory wildlife and shifting sea level rises. Colonization from European settlers forced out this way of land-based living of the Ozinie native peoples. We now live in a modern era of conservation, returning to a form of stewardship, but that of which restricts human interaction to the occasional recreation activity and land stewardship resorted to a few trained park staff with herbicide backpacks.

Modern conservation is a blessing and a curse, on one hand land is returned to public access and protected from further development, though on the other this land now has restrictive use and under “stewardship” practices discerned by the government or land trust, not necessarily that of informed non-toxic traditional ecological practices. Colonization has shaped this island.

Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge, looking into the Chesapeake Bay and Chester River confluence in Fall 2025

Virtual Field Trip: Boreal Forest of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

When your Nordic blood no longer can sweat the sauna of Summer in PA, you migrate north to the refreshment of the Boreal forest in MI! Venture along on a virtual tour of the “UP”, otherwise known as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan; one of our nation’s “best kept secrets” for nature lovers- where botany, berries, birds, and breathtaking lakeside banks delight (and where Finns and Swedes found their home away from home).

Let’s begin down this marshy path just inland from Lake Superior to see what botanical beauties greet us.

Fringed sedge (Carex crinata), Northern Blueflag Iris (Iris versicolor), Wild sarsaparilla (Aralia mudicaulis), Red baneberry (Actaea rubra), Bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis), and Canadian bunchberry (Cornus canadensis) dance upon the forest floor.

Bluebead lily (Clintonia borealis)

Canadian bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

Red baneberry (Actaea rubra)

Fringed sedge (Carex crinata)

Who is munching on this tree over here?... American Beaver!

The American beaver is one of several wildlife species that are commonly spotted when you stay in the UP. Whether you are exploring the waters by kayak or nestled in the woods for an observational hike, wildlife will surely be encountered. Beaver, toads, blue-spotted salamanders, loons, king fishers, eagles, lynx, moose, black bear, weasel, and Waxwing’s favorite- Cedar Waxwings- abound!

American Beaver in the Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park

Cedar Waxwings in the Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park

Exploring further, let’s go out to the sunny, sandy banks of Lake Superior and take notice of more familiar species, also growing in PA’s Piedmont on the cliffs of the Susquehanna Riverlands. What’s growing in these leaner, acidic, fast draining soils?

Northern bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera) stabilizes the sandy banks, Pussytoes (Antennaria howellii), and Crinkled hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa) fill in at roots of high shade trees that have selected the finest real estate along Lake Superior, with million dollar views.

Pussytoes (Antennaria howellii)

Northern bush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera)

Lake Superior’s million dollar views are definitely not consistent, from day to day, often not predictable within the day! As an adolescent body of water, sometimes she is calm and contemplative with loons peacefully diving for dinner and in matter of minutes, rageful with waves of anger that nobody dares to enter (the sinking of The Edmund Fitzgerald ring a bell?).

A freshwater lake that acts like an ocean, carrying 10% of the planet’s fresh surface water. She holds a great responsibility in her waters, despite her young age. What personality do you sense of Lake Superior today as we venture down to the sandy shores and dip our toes into her refreshing, clear waters?

Back into the forest, for the budding foragers and avid agroforesters amongst us. Come be allured by the layered plant community of delectable berries and other forest grown trail snacks. Teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens), a diversity of serviceberry species (Amelanchier spp.), lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), American hazelnut (Corylus americana), and Wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) will only begin to tantalize your tastebuds.

serviceberry species (Amelanchier spp.)

Teaberry (Gaultheria procumbens)

lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium)

American hazelnut (Corylus americana)

To culminate the wild side of our UP trip together, grab 2 liters of water in your pack along with these fueling forest snacks for this next long 10-mile loop. Let’s go explore the final “B” of our trip; the breathtaking banks of the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. Waves, wind, and weathering sculpt these sandstone cliffs. What beauty from such a young artist! Lake Superior is a fairly young glacial melt body of water (even younger than some of our Earth's pyramids!). Do you notice any recognizable botanical beauties that selected the best lakeshore views?

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

As we head back into town to grab a bite to eat and kick up our feet after a full day of hiking with fresh lake air, the ecological gardeners amongst us will appreciate the handiwork of residents and restaurant owners in downtown Marquette, MI. Native plant communities tucked along sidewalks, hellstrips, and historic freighter docking sites.

Marquette, MI

Marquette, MI

Whether you are a botanist, berry picker, birder, or a seeker of breathtaking sculpted lake banks (yes, you can be that ;)), the “UP” is abundant with what your adventurous heart desires. Have you been to the “UP” or itching to fly north for a respite from Summer’s heat? Comment below and/or give this post some shares and love.

Happy continued Summer adventures, ecological gardeners!- Elyse

The Season of Restoration: Spring Musings from Waxwing HQ

It’s official: spring is underway! Birdsong rings out from trees each morning, buds are blossoming, and native spring ephemerals are emerging every day.

Spring ephemerals embody the notion of spring as a season of rebirth. During the summer and colder months, these delicate plants disappear from our view. They retreat underground, where they gather and store energy that will propel them back into the visible world when the next spring arrives. From what appears to be bare ground, new life emerges. Its presence inspires more life-giving activity as insects awaken from their slumber and flit amongst ephemeral blossoms.

A happy bumblebee snacks from Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginiana), a native spring ephemeral that can signify woodland wellbeing

Look up, and you’ll see the same story playing out above our heads. Bare branches suddenly “pop” with thousands of small buds that appear seemingly overnight. One day soon, the brown limbs of deciduous trees will be covered once again in green leaves that offer respite from the warming sun. Songbirds reappear amidst the leaves, perching on once-barren branches before taking flight. Humans emerge from our homes to savor the warming temperatures and enjoy the sights and sounds of spring.

Restoration. That’s what spring reminds us of, and that’s what we commit our energy to here at Waxwing: The restoration of forests, meadows, and other landscapes to their natural way of being. The restoration of biodiversity for ecological resilience. The restoration of ecological memory across diverse landscapes, from urban centers to sprawling meadows and woodlands. The restoration of pollinator habitat and wildlife corridors that enable indigenous plants and wildlife to survive, thrive, and contribute to the ongoing health of our ecosystems. And the restoration of humans’ connection to the land that sustains us and to our own roles within our ecosystems.

As part of this commitment, Waxwing has launched a new service wing focused on Ecological Restoration. Our team is guiding several projects, including Mount Gretna’s (Chautauqua Community) Soldier’s Field Meadow Restoration and the restoration of a 5-acre woodland tucked into a suburban community in Lititiz.

A “before” photo from the woodland, which was overrun with invasive honeysuckle and other displaced species that prevented the growth of indigenous plants

When Waxwing was first called to the woodland, it was overgrown with displaced, fast-spreading plants including bush honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), privet (Ligastrum spp.), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), honeysuckle ivy (Lonicera japonica), and yellow archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon). These plants covered the forest floor and filled the understory, preventing the growth of native plants—the wise elders of the ecosystem—and harming the woodland’s ecological wellbeing.

Our team began removing invasive plants—species that have been introduced and struggle to co-exist with the biodiversity that our ecosystems are capable of supporting—in December 2024. We return to the woodland weekly to continue this phase of the project.

Working section by section, we first remove undesirable woody shrubs followed by undesirable groundcovers. As always, our methods are 100% chemical-free, making this process safe for people, pets, and wildlife. We follow the removal process by densely seeding with native plant seeds.

A model or reference ecosystem: Over time, the Waxwing team hopes to restore the Lititz woodland to something approximating this scene from Lancaster’s Ferncliff Wildlife & Wildflower Preserve, which bursts with native spring ephemerals and other plants that are indigenous to Pennsylvania forests

Over time and with ongoing stewardship, the composition of this woodland’s midlayer and understory will shift to feature native shrubs, herbaceous perennials, and groundcovers. This will restore habitat and food sources for countless insects, birds, and other wild creatures, returning the woodland and its inhabitants to greater health and resiliency. It will also create more opportunities for humans to connect with nature and find our own place in the forest. This is a long-term, multi-year project and a true labor of love on the part of the homeowners and the Waxwing team: love for our woodlands and love for all the creatures who rely on them for shelter and sustenance.

In that same spirit of love, we here at Waxwing wish you and your gardens a restorative spring!

Rebuilding Biodiversity Through Hands-On Participation

Waxwing’s mission was generated from the heart. In all the ecological services we provide (gardening, restoration, and education), it is essential that we involve YOU. Your observations, vision, and hands-on participation. Why? We believe that participation builds a compassionate culture within our community that is needed to reverse the biodiversity crisis.

Some say that this is bad business. We teach our customers how to exactly do our services; lawn conversions, non-chemical invasive removal, etc. What may seem like bad business ends up fueling a movement that feeds back into our mission. Those that are patiently waiting for their ecological project designs understand that in fact business is thriving. Habitat building work is in hot demand, in gratitude to you being inspired after a productive work day and sharing your enthusiasm within your communities!

Captured here are two photo journalism stories taken place this Fall. The first featuring our Ecological Garden “wing” (Blossom Hill Mennonite Church) and the second series of photos showcasing our New! Ecological Restoration “wing” (Mount Gretna Meadow Restoration). Enjoy perusing our community’s participation!

Blossom Hill Mennonite Church (Phase I)

Blossom Hill Mennonite congregation gathered in early November 2024 to impressively sheet mulch over 4,000 square feet of underutilized lawn. A “soft landing” under a beautiful oak was site prepped, along with 2 other large pods with 10 ft. sweeping mowable paths interweaved. We are all excited for Spring 2025, when thousands of beautiful native blossoms will be plugged for beauty and biodiversity.

Congrats Blossom Hill for faithfully muscling through Phase I! Grateful for the Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake Bay for their financial contributions to help make this “building biodiversity” vision come to fruition.

Mount Gretna Meadow Restoration (Phase I)

This week we accomplished Phase I of Mount Gretna’s (Chautauqua Community) Soldier’s Field Meadow Restoration. The nearly 1-acre of beautiful existing little bluestem, broomsedge, poverty oat grass, and pockets of pussytoes meadow is pressured by adjacent cool season field fescues and foxtail. We worked a solid 7 hrs. hand digging out these less ecologically valuable species and creating openings that will receive a colorful custom made PA eco-type seed mix in February 2025. Non-chemical interventions and education to support the ecological literacy of the community is this “building biodiversity” project’s focus. The 3 visiting bluebirds approved of our non-toxic techniques!

Congrats on impressively muscling through Phase I, members of Mount Gretna and Chautauqua communities!

Do you have a community project that needs a facilitator to guide educational outreach and an ecological service? We would love to collaborate with you to bring ease into the planning and expedite the opportunity to heal our communities and build beautiful habitats!

Reference Landscapes | A Guide for Ecological Gardeners

In the planting lull of Summer, the Waxwing crew enjoys botanizing at some regional ecosystem hot spots. These special spaces are rich in biodiversity and serve as a reference landscape in our native gardening and restoration practices. Guides for our ecological design process.

According to the Society of Ecological Restoration, an internationally acclaimed community of practioners that set global standards for building biodiversity with both social and ecological benefits, reference landscapes are models that help to “identify and communicate a shared vision of project targets and specific ecological attributes”. Abiotic and biotic conditions are considered when analyzing this reference ecosystem- how water flows (hydrology) and disturbance cycles (fire ecology, etc.) are some examples of abiotic or non-living attributes, in addition to species composition, their structure, and any successional characteristics specific to this site.

Join us on a virtual field trip of three ecological reference landscape pilgrimmges: New York’s Adirondack Mountains, New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, and Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains. These spaces are inspiration to us as ecological designers, stepping into a healthy habitat, exploring how ideally our rebuilt ecosystems should feel and function.

Adirondack Mountains

New York’s ADK’s are characterized by a mix of mountains and lakes, nestled in a transition zone between deciduous and boreal forest biomes, supporting an exceptionally rich diversity of flora and fauna.

Bunch berry (Cornus canadensis), turtlehead (Chelone glabra), and plantain sedge (Carex plantaginea) were some of the memorable flora on this primitive camping and hiking trip. Explore beaver built wetlands and hike to the top of Mt. Marcy to see a rainbow, in this virtual field trip below!

Pine BARRENS

New Jersey’s Pine Barrens are a large mosaic of contiguous forest and wetland habitats composed of acidic coastal plain sands/silts/gravels. Species that thrive in low-nutrients and with fire are found in this ecosystem.

Huckleberry (Gaylussacia spp.), summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), and hyssopleaf thoroughwort (Eupatorium hyssopifolium) were some of the memorable flora on this primitive camping and hiking trip. Explore scrumptious berry patches and tannic lakes in this virtual field trip below!

Allegheny MOUNTAINS

Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains, composing the state’s only national forest, is characterized by mixed hardwood tree species and are known to support more rare populations of fireflies (that synchronize their light!).

Roadside scarlet beebalm (Monarda didyma), boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), and purple-flowering raspberry (Rubus odoratus) were some of the memorable flora on this primitive camping and hiking trip. Venture barefoot through creekside groundcovers and swoon over ferny textured rock outcroppings in this virtual field trip below!

What regional ecosystems guide how you design, build, and steward your homegrown habitats? Let’s make a list of reference landscapes for Waxwingers to explore. Share and comment below!

Ecological Memory | Awakening What Was Thought To Be Lost

When facilitating the Habitat Advocates and Ecological Gardener Training programs, I am often questioned about the quandaries of how to ecologically approach land that is inundated with assertive introduced species, like; bush honeysuckle, lesser celandine, and stilt grass.

Emotions and energy are often peaked, accompanied with well intentioned focus to immediately eradicate these increasingly common areas where we live, work, learn, play, and worship. My response to this inquiry is one that is not often desired.

First, we must take a deep breathe and then, OBSERVE.

Lesser celandine (Ficaria verna) along the Little Conestoga River @Waxwing HQ, Lancaster PA.

“Gahhh!” I can hear you gasp, as you see this unwelcomed sea of yellow. Why not immediately react?

At the new Waxwing HQ, observation has been crucial over this first year residing along the Little Conestoga flood banks. An expected flush (approximately 1/4 acre) of lesser celandine (Ficaria verna) occurred throughout the floodplain in Spring 23’. Expected given that the small, dormant bulblets (or bulbils) were observed when walking the site during the house walk-throughs in Fall 22’. Obviously it didn’t disuade me.

A 6-inch spicebush gave me heaps of hope.

I know what you are thinking… spicebush!?!… they are a dime a dozen! But here along the impaired banks of the Little Conestoga, less ecologically interactive species, like bush honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), dominant the shrub layer, so a little native gem like this is something to celebrate!

This is ecological memory.

Lindera benzoin (spicebush) growing amidst lesser celandine flush.

Due to the inability of lesser celandine to play well with others in this region, with factors out of its control- no natural predators- and some tenacious survivability traits of the species (bulblets and early spring presence), lesser celandine will spread readily, decreasing the biodiversity in its path.

If my response was to react to its uncontrollable nature with glyphosate, a common restoration ecology practice with invasive species, this baby spicebush (and dozens that have been found since), along with other highly beneficial native species would have been lost. It’s like the old medical adage of dosing a wound with rubbing alcohol, now highly discouraged; the repair that you think you are doing to the system may in fact be impairing its ability to heal long-term. Nuking a site isn’t creating a path towards resilience.

In our chosen ecological practice, other than mowing navigation paths throughout the floodplain, all other areas were left unmowed to flush out any intact internal memory (ie; seedbank). By taking the unconventional path of not spraying and leaving ample no-mow areas, in Spring of ‘23, a more desired flush occurred.

What memory was awakened? Spring beauties, Sedges, Fleabanes, Violets, Honewort, and Mayapples! This is why we pause and observe.

Spring beauties and violets in the seedbank @ Waxwing HQ.

Fleabane and violets in the seedbank @ Waxwing HQ.

Mayapples in the seedbank @ Waxwing HQ.

Interestingly the spaces where these botanical lovelies popped up were likely left suppressed for decades. Formerly, this space was routinely mowed. Dozens of native species have since been documented, in just 1 year of “no mow analysis”.

Although in the case of many suburban lawns, exhibited by many of Waxwing’s customers, the ecological memory has been almost entirely lost (aka: ecological amnesia). Lawn sprays, soil compacting mowers, or simply the initial developers removing the intact topsoil of the neighborhood contributes to this loss. A year of no mow analysis is unnecessary and may in fact be harmful to the intended ecological pursuits in these human dominated spaces. A full habitat revamp (minus the few hearty violets and sedges found) is often needed by smothering the lawn and designing a native plant palette, inspired by naturally occurring native plant communities.

No mow floodplain areas along the Little Conestoga @ Waxwing HQ.

As exhibited, within spaces like this floodplain at Waxwing HQ, there could be treasure troves of hidden natives that may simply need a little (or a lot) of non-chemical TLC. What these types of spaces don’t need is reactionary spraying that will only create additional quandaries of erosion and loss of cover for wildlife. After observation, it becomes apparent that a phased plan is needed, combining conscious removal, outcompeting in patches with select native species, and bolstering with larger sweeps of a designed site-specific native plant community. A simple dichotomous key decision tree for taking action in these increasingly common spaces can be found below;

In my training courses, we simply use a Venn Diagram to determine the characteristics that capitalizes on the difference of the undesired competing species, leading to a list of high functioning native plant species that can hold a candle, or better yet, fully outcompete the less desired, poor ecologically performing species. Again, without needing to use chemicals, like glyphosate, that the EPA has reported harms 93% of endangered species (and you).

The “bolster the banks” of the Little Conestoga experimental project began in Fall 22’ (with phased extension plantings since), a spot predominated by lesser celandine and another uninvited guest, goutweed. The ecologically underperforming introduced species were manually removed via a broadfork (bulbets of celandine still present). This was conducted after initial observation of existing populations of wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), and wingstem (Verbesenia alternatifoia) that seemingly were not outcompeting the goutweed, though each holding a vibrant candle. A small test patch was planted by immediately chasing with semi-evergreen and other hardy native plants like tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia cespitosa), cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata), Germander (Teucrium canadense), a variety of semi-evergreen sedges (Carex spp.)., and Packera aurea (golden groundsel)- a species in the wholesale trade whose genetics exhibit a more rhizomatic tendency than its more timid local ecotype cousin in the piedmont of PA. A favorable genetic attribute for ecological restoration folk? Perhaps a question for a separate blog post. Several of these species hold a characteristic- being evergreen- a trait not exhibited in lesser celandine.

The idea being that instead of haphazardly nuking our poor ecologically performing sites, a small and slow (my fav Permaculture principle) solution is trialed, ensuring long-term manageability of site and respect to the nursery people, plants, and your pocket!

Best practice is to first small patch test, then scale up if resources allow.

Deschampsia cespitosa and a variety of semi-evergreen Carex species (a little Lobelia cardinalis peppered throughout) planted as a test restoration plot along the Little Conestoga.

More insight over the last 4 years has been gleaned on a larger site along the Lititz Springs with Packera experimentation (and other native ally species), with a Waxwing co-stewarding customer (a monthly service offered for inquiring customers that seek to steward their properties alongside a trusted professional). Where once lesser celandine flushed out in full glory, Packera and other allies now reside. Those that know my favorite native plant allies, won’t be surprised that sedges (I can hear the latest Habitat Advocate graduates chuckling ;)) take precedence as well. Wild oats (Chasmanthium latifolium), hoary mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), wild ryes (Elymus spp.), and several of the other trialed species were then later discovered on Nancy Lawson’s helpful guide of “How to Gently Fight Plants with Plants”.

Waxwing planting of Packera aurea, along the banks of Littiz Springs. Lititz, PA.

Waxwing planting of a diversity of Native Plant Allies, along the banks of Littiz Springs. Lititz, PA.

As part of the Ecological Gardener Training program, in collaboration with the Horn Farm Center, we study these stewarding techniques of mindful removal of invasives and competitive exclusion to encourage the ecological memory residing within the novel ecosystems growing at the Horn Farm.

Throughout the 16-week hands-on training, our learning adventures begins with observation of intact thriving ecosystems, to site analysis, to research and design, then ultimately to bolstering a site. The site cases for the 2023 cohort exhibited many bare soil gaps after selective hand pulling of invasives. Trainees enhanced the tapestry of interactions by selecting species that mingled well with those unveiled and also exhibited characteristics that would give them a leg up in considering the competitive exclusion principle (yes, my favorite, sedges, were on the list!). Trainees use resources like the Terrestrial and Palustrine Plant Communities of Pennsylvania, which help inspire the handy Hungry Hook’s Plant Community’s Key, to discern which species can bolster a site that was formerly site prepped via hand removal of invasives species.

Highly disturbed spaces may appear at quick glance that they lack the ability to rebuild complex ecological interactions, however with a calm and compassionate human hand, robust levels of resilient native species, whether internally or encouraged from adjacent ecosystems, can awaken the ecology that once was vibrant and thriving. Let’s be agents of unearthing ecological memory, ecological gardeners!

Ecological Gardener Training Program at the Horn Farm, 2023 cohort. Assessing ecological memory and bolstering the habitat with site-specific native plugs. York, PA

Have you engaged in non-chemical ecological stewarding? Do you love experimenting with outcompeting undesired invasive plants with ecological robust native plants? Give the post some “Love”, “Share” with a friend, and/or comment below! Thank you :).

Keystone Species | Oaks, Goldenrods, American Beaver, and Humans?

As ecological gardeners, we grow to know and love “keystone species'“ of the Plant Kingdom, scientifically found to support the greatest number of Lepidoptera (the caterpillars of moths and butterflies). For the herbaceous plants in Eastern Temperate Forests, the top 3 performers are: Goldenrods (Solidago spp.), Asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), and Perennial sunflowers (Helianthus spp.). Douglas Tallamy is claim to fame for crediting Oaks (Quercus spp.) for being the keystones of the woody world, along with wild cherries (Prunus spp.) and birches (Betula spp.).

Solidago graminifolia in a Waxwing garden

Helianthus occidentalis ssp. dowelianus in a Waxwing garden

Symphotrichum oblongifolium ‘October Skies’ in a Waxwing garden

As defined by Britannica encyclopedia, keystone species have a “disproportionately large effect on the communities in which it occurs. Such species help to maintain local biodiversity with a community either by controlling populations of other species that would otherwise dominate the community or by providing critical resources for a wide range of species”.

The imagery of this essential stone in a classically crafted arch for bridge construction, coined by American zoologist- Robert T. Paine in 1969, helps to conceptualize the dependency that the majority of the other stones have on this key piece.

Keystone. Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keystone_%28architecture%29

Likewise, a disproportionately large number of Lepidoptera species are dependent on a select few keystone native plants species. These species are like the red block, pictured above, powerhouses for wildlife, fueling a large percentage of your backyard habitat’s food web.

On a more macro level, within the Animal Kingdom, beavers are deemed the movers and shakers within ecosystems of our region. Bolstering biodiversity by creating wetland ecosystems along waterways, increasing habitat for a large variety of flora and fauna. Without the beaver, more stormwater rushes through landscapes, without having the opportunity to slow down and recharge the water table. The arch collapses.

A pair of young beavers. Image source: https://www.bayjournal.com/columns/chesapeake_born/leave-it-to-beavers-species-ability-to-alter-land-should-be-revisited/article_d587a939-1f8e-58c4-92ea-b74a97538259.html

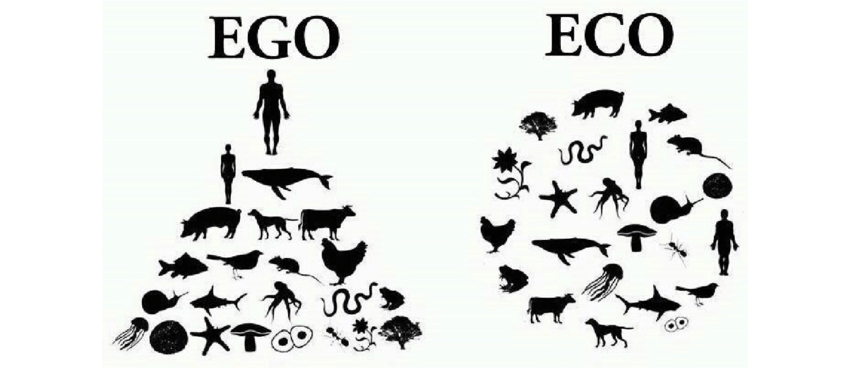

So, the question begs, as the title of this blog suggests, are humans also keystone species? This is a struggle for some of us to ponder and it may stem from this imagery that has sorely been our egotistical understanding ourselves on planet Earth. Humans as habitat destroyer, mountain mover, land paver, resource extractor, and water polluter.

The misconceived thought that the planet is for us and for us only. Within our ecological gardener community, some of us may not be at peace with our species, stemming from many of our recent collective and destructive choices as a species. We are in fact living in the “Age of the Anthropocene” after all.

“Ego-Eco”. Image source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagram-Ego-Eco-Humankind-is-part-of-the-ecosystem-not-apart-from-or-above-it-This_fig1_330697869

Will we embrace an “eco” paradigm shift, where we humbly see ourselves as one species within a rich tapestry of diversity on Earth? A way of life demonstrated by other human cultures for thousands of years. Will we heal our relationship within our own species, accepting the stories that were left to fully sculpt the character of our species, and to craft new stories of healing and reciprocity?

Note: To dig deeper into the concept of reciprocity, please if you haven’t done so already, do check out “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Kimmerer- life changing for many ecological gardeners. Side story: When I met her at a recent book talk event, I felt so compelled to give her a gift, in exchange for all the rich gifts she shares, in word, in this book. So, I gave her the only thing I had with me, a Waxwing canvas tote bag and left with my signed book all speechless and swoony. Those who know me, I’m not one for being left starstruck <blushes>.

Lancaster city youth watering raised container native mini-meadows to support greening effort on their block.- Spring ‘22

Will we heal from our past destructive action? Will our healing within our own species go so deep that we then give back and fundamentally restore the natural systems that have sustained us so generously?

If so, will we then go as far to say we are a “keystone species” in this new era? A species that is so pivotal to the future of our planet; our intellect so key, so vital in rebuilding biodiversity on planet Earth? Helping broken soils (American’s herbicide lawns!) remember who they once were and to possibly even create intensely genetically rich gardens, backed by compiled entomological research to support Lepidoptera in ways only a human could research and craft? Beautiful demonstration of this recently brought to fruition at the Arboretum at Penn State!). Field trip anyone?

Arboretum at Penn State, Phyto Studio. Image source: https://www.phytostudio.com/psu

Is the survival of the Monarch butterfly highly dependent upon Homo sapiens sapiens? Is the preservation of the memorable song of a wood thrush in the hands of humans? Is the health of waterways and access to clean drinking water pivotal on the action of our species? Is the continuation and necessary bolstering of the biodiversity of our national forests, state forests, public lands dependent upon us? Are we a key stone in this bridge to the future of the planet?

Last question, I promise ;). Is the act of saying “yes” to all of the above “ego” or “eco”? If we move forward with acceptance of this vital role to play as earth citizens with fascinating intellects, empathy to offer, and sweat to outpour, then it can be argued its the most humbling of pursuits.

“Wild Plant Culture” by Jared Rosenbaum.

Jared Rosenbaum, author of recent book release, “Wild Plant Culture: A guide to Restoring Edible and Medicinal Native Plant Communities”, beautifully and poignantly calls humans to be keystone animals that steward and tend diverse wild communities. The greatest quest, he shares, is to “fully integrate the most challenging animal of all- the human being- into our native plant gardens”. We can do so by informing our actions through traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), a cultural practice with the land that has unfortunately lost its way in European colonization.

To culminate this concept of embracing human as “keystone”, let’s take it one step further. Do we also feed ourselves with the native plants that we bolster are backyards with? This lens is very easy to swallow for the lifelong forager or proud permaculturist, but maybe not as easy to embrace for the ecological gardener that came to this practice in deep empathy for wildlife, not their own species. Arguably, it is essential to first build back biodiversity for the other-than-human species; to feed our struggling kin, before feeding oneself, who has historically taken for generations.

Though once we have enriched our human spaces with that initial motivation to rebound wildlife populations, can we then feed ourselves with the same rich fruits, seeds, nuts, and greens? Not to be confused with unsustainably taking from dwindling wildlife populations’ essential food sources; again, they dine first. We have conventional ag, unlike our coevolved wildlife kin that only can eat native plants. Groceries/markets are our transition until we can sustain fully perennial native edible landscapes. Will we respect our species- humans- to the full extent of enriching our cells also with the plants that our wildlife friends and, of course, our indigenous kin once too sustained on?

Mountain mint in a patio pot at Waxwing’s first HQ in Lancaster city.

It turns out that when we consciously choose to steward habitats for wildlife AND also for our sustenance, we immerse ourselves fully as being part of nature, not separate from it. And when that happens, we can then begin to see ourselves as a “keystone species”. Doesn’t that just make you want to jump up and dig some pawpaws and medicinal mountain mint into the earth?

We can “free to birds with one hand”, by choosing to consciously plant species that not only are native and high yielding for wildlife, but also happen to be highly nourishing for humans too! So, if you’ve never eaten a wild perennial plant and are thinking, how on earth would I even start on this adventure? Well, don’t start with mushrooms ;) . I suggest to my customers to begin with “low hanging fruit”, a wild food that tastes good, freshly picked off the plant, that doesn’t need preparation.

Backyard harvested serviceberries at Waxwing’s first HQ in Lancaster city.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)- pick and eat those antioxidants! I promise the tree has more fruit than wildlife can eat, I often pick fruit along with the squirrels and cedar waxwings higher in the branches, we all dine collectively. You are the keystone, plant that tree.

Here’s a cool example for those that love to stack a boat load of functions into their actions… plant AND eat anise-scented goldenrod (Solidago odora). Its a KEYSTONE native herbaceous plant AND a nutritious little topper to your salad. Check those leaves to give the baby Lepidoptera first dibs!

One last example to toast the human quest of healing our understanding, our role, in this building back biodiversity adventure. American plum (Prunus americana), a keystone native plant AND a caloric fruit packed with vitamin A, K, B5, C, and potassium. A shout out to friend and Waxwing contractor, Donna, and her edible native nursery, Fernwey, for making this homemade American plum wine. Raise a glass- be well in this new year keystone kin!

American plum (Prunus americana) wine, made by Donna in a 2022 wine-making workshop at Rising Locust Farm.

Have you embraced the role of being a keystone species? Do you love munchin’ and crunchin’ on native plants? Give the post some “Love”, share with a friend, and/or comment below!

Governor Dick Park | "This Reminds Me Of..."

Waxwing crew conducting field research in Fall 2022 | Govenor Dick Park, Manheim PA

The Waxwing Crew explored Governor Dick Park this Fall, as part of a short series of field research and foraging hikes, enriching our work as ecological gardeners. With iNaturalist in hand, we began on a moderately slow “botanizing” hike, stopping at every green texture or splash of color along the trail that was new to our eye. As members of the Muhlenberg Botanical Society, a local group of native plant enthusiasts and self taught botanists, we knew that “slow-n-steady” results in the best forest finds ;).

Green Dragon (Arisaema dracontium) | Govenor Dick Park, Manheim, PA

Green Dragon (Arisaema dracontium) | Govenor Dick Park, Manheim, PA

Our adventures started off strong when not long into our loop hike we spotted this stunning Green Dragon (Arisaema dracontium) along the trail, thanks to Derek Metacalfe, Fall 22’ intern, nicknamed Gymnocladus metacalfe, or Gymno for short. Note: when working with Waxwing over a substantial length of time, you eventually acquire a botanical nickname. Hmmm… I’m sensing this will likely need to be a future blog post. Yes, there are actual rules to this nicknaming game ;).

I found it fascinating that Gymno connected with this plant when we first spotted it by immediately sharing, “This reminds me of Jack-in-the-Pulpit…”. Fascinatingly, the Green Dragon plant shares the same Genus as Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum).

As an environmental educator, I often ask younger scholars, “What does this remind you of?”, a gentle way to guide learners into reconnecting their relationship with nature. A John Muir Laws tip that never disappoints. However, the “this reminds me of” pedagogical trick when working with youth doesn’t always work out so seamlessly scientific, as illustrated with this Green Dragon example ;).

Citronella horse balm (Collinsonia canadensis) | Govenor Dick Park, Manheim, PA

This next forest find elicited a collective “This reminds me of…”, after giving the foliage and flowers a gingerly scratch-n-sniff. <Breathe in>…. ahhhhh, bright notes of citronella! In this case, our connection to the plant led us to help ID it through one of its common “street” names, Citronella horse balm. Citronella horse balm, or its formal scientific name, Collinsonia canadensis, is found in rich, moist woodlands, acting as good late season nectar and pollen plant for bees, a host plant for several species of Lepidoptera, and a medicinal forest tea for the curious forager.

Which of the local wholesale native nurseries want to start flushing these out as plugs? I know a few Waxwingers that would love to pepper their woodland gardens with these scented delights!

Still determining species (Erechtites or Lactuca?) | Governor Dick Park, Manheim, PA

As we continued on the trail, we approached a forest clearing where 4 ft. fluffy white seed heads stood boldly as a community. “This me reminds me of wild lettuce!”, I shared with the crew. We humbly approach the charismatic plant, feeling a bit perplexed. Still puzzled, we look to iNaturalist for help. Snap a few pictures and submit. American burnweed (Erechtites hieraciifolius), it suggests.

Laura Newcomer, Fall 22’ intern, otherwise known as Kalmia newcomerium. Get it? Mountain laurel… Laura. Ooook, teaser alert! The way the botanical nicknaming game works, via Waxwing rules, is that 50% of your nickname must be legit, a real Genus or a real species. The remaining part of the botanical nickname must connect with your human name. So, Kalmia (real Genus) and newcomerium (alluding to her last name). Its that simple and yes as joyous as it sounds, so give it a try with your nerdy native plant friends!

So, continuing with the story, Kalmia connects to the plant sharing that she recently saw wild lettuce (Lactuca canadensis) at Sherrie Moyer’s nursery, a friend and owner of Hungry Hook Nursery. Sherrie (Botanical nickname TBD, how did she manage to skate by acquiring a botanical nickname?) and I have have casually collected seed on a hike in this location in the past, so the gears start rollin’.

Afterwards, when reaching out to Sherrie to help with identification, my pictures made for a toss up of either Lactuca, or the iNaturalist suggested, Erechtites. More pictures are needed to clarify the beauty’s name. Until that day, the fun, fluffy white seed heads and distinct habit of courageously growing as a community, will be how I resonate with this plant.

Donna Volles nibbling Wild Oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) | Govenor Dick Park Manheim, PA

As we journeyed through the forest, gathering pawpaw (Asimina triloba) snacks, we culminated our “field trip Friday” in the native meadow at Govenor Dick Park. Waxwing contractor and owner of Fernwey Native Nursery, Donna Volles, aka Monarda didymadonna or Didymadonna for short, made a beeline to the Wild Oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) and gave it a nibble, as any good native edible nursery owner would do ;).

This plant reminds me of when I first intensively studied native plants as part of my Mt. Cuba certification training. I needed to creatively cement the scientific names leading up to the big test days and of course to carry this skill into my business practice. I distinctly remember greeting Wild Oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) for the first time and picturing a skateboarding boy with chevron markings (the distinct seed head design of this plant) shaved into his hairdo, heading off to school with a belly full of hearty oats. In my mind the plant says, “Hi! My name is Chas, “the man”, and I ate wild oats this morning for breakfast! Cya latifolium!”.

Not how your brain works? For the seriously scientific among us, your best bet would be to use the Latin root words the original botanist utilized to identify the plant. For the Chas example here, according to the Missouri Botanical Garden, “Genus name comes from the Greek chasme meaning gaping and anthemum meaning flower for the form of the flower. Specific epithet means broad-leaved”. Other common Latin roots to get you started can be found here.

Waxwing crew researching and observing their native meadow plant finds | Governor Dick Park, Manheim, PA

Next time you are out on a botanizing adventure and wonder about the identification of a plant. Use the connecting question tool of “What does this remind me of?” to start rebuilding your tie to the plant. What story does it tell you, seriously or silly? What of their relatives may you have met before? What of their characteristics do you resonate with? As ecological gardeners, we know the “more-than-human” world has a lot to teach us. We simply need to pause with them and listen.

Do you enjoy connecting with native plants, learning new pedagogical tools, and/or appreciate public lands to explore like Governor Dick Park? Give the post some “Love”, share with a friend, and/or comment below!

Moth ID | Exploring the "Deep Sea" of the Forest

This Summer I participated in the Moth Lighting at Climbers Run Nature Center, as part of a collaborative event of the Lancaster Conservancy and budding professional community- the Ecological Landscaping Guild of the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed. Keith Williams, Naturalist and Community Engagement Coordinator for the Lancaster Conservancy, and Ian Gardner, of Green Gardner Designs, facilitated the night’s public event.

Keith Williams (left) and Ian Gardner (right), facilitators of the Moth Lighting public event @ Climbers Run Nature Center- July 2022.

Using simply a white bed sheet and lighting (mimicking the moon’s glow), dozens of species were attracted to the staged observation space over the course of the night. Large Catalpa Sphinx Moths and more delicate Angle Wing Moths arrived in shifts, pausing calmly on the sheet as if they “had arrived”. Entomologists speculate that the glow of the staged light, resembles the glow of the moon, which is a moth’s navigation tool when in flight. Positive phototaxis, or the phenomenon of nocturnally active moths being attracted to light, allows naturalist to use the man-made light to lure them for ease in identifying the species.

A simple white bed sheet and hung lighting to set the stage for the night-flying moths @ Climbers Run Nature Center.

The man-made lighting illuminated at night.

Identifying the diversity of moths in a habitat (designed or in the semi-wild) is valuable information to gather, given that Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) are the basis of an ecological food web. The richer the species in diversity and quantity, the stronger the resilience the space has in fueling a web of life.

Night-flying moths are often neglected in an ecological gardener’s observation and consideration when anecdotally assessing the biological health of their space, presumptive of the fact that you need to stay up after dark (I come by this honestly) in order to make that assessment. Possibly also the duller colored patterns of their camouflaged wings make for a less spectacular identification experience than when identifying colorful butterflies on one’s property. In either case, moth identification is a rarely explored world, a deep sea dive experience per say of our backyards and forests.

Identifying a Catalpa Sphinx Moth @ Climbers Run Nature Preserve

As the dark night hours drew on approaching 10:30, 11pm, the naturalist jokes started to brew and chuckles filled the forest air. Looking up the names of the moths as they flew into sight; ; Pawpaw Sphinx Moth, Catalpa Sphinx Moth, Common Oak Moth, etc. Maybe they too were a bit delirious in the depths of night when making these discoveries, lacking a bit of creativity. Although in a way, several of their matter of fact names alluded to their host plant, useful as a beginner moth identifier.

Catalpa Sphinx Moth caterpillars on their host plant in Lancaster County Central Park- July 2022.

The Catalpa Sphinx Moth was a particularly intriguing identification not only for their large stature compared to the other moths we witnessed, but to the serendipitous correlation I made in a recent discovery when hiking in Lancaster County Central Park, just under a week prior this event. As pictured above, dozens of hungry caterpillars were munching on a Catalpa tree. I snapped a quick picture, thought for a moment “these are definitely moth caterpillars”, and neglected to upload it on iNaturalist for suggested identification. Zoom forward to the late night epiphany at the Moth ID event- turns out they were Catalpa Sphinx caterpillars! It was a delight to witness them in these two distinct phases of their lifecycle!

Additional moth identification photos from the Moth Lighting @ Climbers Run Nature Center public event…

Do you love Lepidoptera and/or appreciate public environmental education events hosted by the Lancaster Conservancy, like this Moth Lighting event? Give the post some “Love”, share with a friend, and/or comment below!

Mimicking the Mycelium Network | Welcoming New Waxwingers

Supporting the growing ecological gardening field is much like working to build the rich fungal soils of a forest. It is complex, layered, and takes time. Like mimicking the mycelium network in forest soils, we need to nurture integral connections between each other to meet the immediate demands of wildlife, the heartfelt native habitat requests of customers, and to sustain the well-being of a growing demand of trained ecological gardening contractors.

In order to start building the “fungal soils” of the professional ecological gardening world in the Lower Susquehanna River Watershed, Waxwing EcoWorks is training two contractors this year, as part of the Ecological Gardener Training, in collaboration with the Horn Farm Center. These contractors are participating in a 16-week hands-on intensive training that enriches their baseline ecological knowledge, observation, and fundamental skills in ecological gardening site prep, design, and stewarding.

This training, along with field experience on Waxwing project sites, will help build resilience in a field where workforce capacity does not meet current service demand. Each year, the aim is for the Ecological Gardener Training and internship experience to contribute in a small, yet direct way in bolstering this growing ecological service industry.

Please welcome and meet the new Waxwingers for the 2022 Spring Season!

Rebecca Knappenberger | Ecological Gardener Intern

“I mostly grew up in rural western Pennsylvania, surrounded by trees, and a short drive from old growth forests. My love for nature started young, with regular family camping trips, hikes, and river wading.

My husband and I moved to Lancaster city over 10 years ago, and have since grown to love this region--though its agricultural landscape is quite different from what either of us were accustomed to.

I've been grateful to learn of local organizations like the Lancaster Conservancy, who work to preserve our wild lands and ecosystems. Last year, I had the opportunity to work as one of their seasonal Interpretive Rangers, and it further inspired me to grow in my knowledge of native plants and habitat.

I started reading Douglas Tallamy's "Bringing Nature Home," and quickly resonated with his vision for suburban landscapes: landscapes no longer dominated by vast expanses of mowed lawn, but instead intentionally filled with native plants that support local ecosystems. I would love to see more people catch this vision, and join in the effort to support our environment in deeply needed ways.

My goal for our own lawn is to have less and less to mow. So far, we've planted 7 trees, along with many native shrubs & perennials. I'm eager to further design our green space with the skills learned throughout my internship with Waxwing Ecoworks Co., and to help equip others to do the same.

My professional work experience has predominantly been within the realm of social services, but I see how investing in healthier natural environments is also an investment in healthier neighborhoods. We all need vibrant green spaces to thrive. “

Donna Volles | Ecological Gardener Contractor

“Donna (she/hers) has been committed to regenerative Earth work as a career path since 2018. Her passion lies in plants, collaboration, and community resilience. Donna has been practicing gardening, farming, herbalism, preservation, nutrition, plant/fungi ID, and gathering with reciprocity for a decade.

She received her Permaculture Design Certificate in 2013 from Wilson Alvarez and Benjamin Weiss and has studied with Ja Schindler of Fungi for the People, Dave Jacke, Sandor Katz, and numerous others regarding plant propagation, pruning, and tending fruit trees. She is also a Habitat Steward through the National Wildlife Federation and soon to be a certified Ecological Gardener. Her last five years were spent living collectively and working collaboratively at Rising Locust Farm, a small scale regenerative ag farm located in Manheim, PA. She is the mother of one beautiful, gentle, curious child.

Most recently, Donna has started Fernwey, a licensed small-scale plant nursery specializing in edible perennials, both native and non-native as well as hardy, adaptable selections of native shrubs and trees. Fernwey seeks to help facilitate human reconnection to natural systems, improve soil and water quality, restore diverse, native habitat to the ecoregion, while providing abundant food sources to all of Earths' inhabitants.”

Tyler Snelbaker | Ecological Gardener Contractor

"I grew up in Dover PA, a semi-rural suburb of York. I have always had a love of nature and spent many summers playing in the creek across the street from my house. I feel more comfortable in the forest than at the beach. I love the trees, the shade and oxygen they create. I have witnessed a lot of development in York County in the last 32 years and I started a business to restore some of the developed land to bring back some of the ecosystems that were destroyed or damaged.

I started a business called Restoring Creation Land Care LLC to do just that, using native plants and organic land conservation techniques to restore habitat by decreasing lawn size in favor of beneficial plants for wildlife and pollinators, also working to add rain gardens to prevent excess runoff, erosion, and flooding downstream.

I’m currently a student in the Ecological Gardener Training program that Elyse is teaching and completed the Chesapeake Bay Landscape Professional training. I also have a background in Physical Therapy as I studied to be a Physical Therapist Assistant before finding and pursuing my love for conservation landscaping.

I have two children 4 and 6 years old who also love nature and they love to learn and help plant trees and dig in the yard. We now live in York city and enjoy volunteering in the community. We helped plant several community garden projects at Kiwanis lake and in our neighborhood that were organized by the Audubon Society of PA. I get a lot of fulfillment out of giving back to Mother Earth and getting a feeling of helping restore balance to the environment.”

by Elyse Jurgen | Waxwing EcoWorks Owner/Founder

Are you an ecological gardening service provider, also experiencing the need of a well trained, nurtured workforce? Share your experience/comments below and give this post some love. Thank you!

Clark Nature Preserve | Observing Winter Interest and Sociability

Nestled in the river hills of the Susquehanna River, the Clark Nature Preserve, stewarded by the Lancaster Conservancy, is home to a diversity of ecosystems awaiting your exploration! The seeded meadow, with its circuitous wide trails, is exceptional to witness in the winter. The meadow is part of a reestablishment effort of predominately native grasses and a handful of forbs, where conventional agricultural fields once stood. The PA Game Commission and the National Wild Turkey Federation partnered with the Conservancy on this effort.

Meadow trail marker with wild bergamot seedheads (Monarda fistulosa) | Clark Nature Preserve in Pequea, PA, January 2022

Whether you explore by snow boots or cross-country ski boots, the paths pass by stark pops of textured seed-heads that catch your eye between the seas of high grass and early successional trees, their rarity forces you to pause <breathe>. The sunlight dancing between the tawny thatch, the varied sepia notes satisfying your warmed Winter soul, just as it does even on the most color poppin’ Summer day.

Wild bergamot and goldenrod species highlighted in a matrix of tall grasses and early successional trees | Clark Nature Preserve in Pequea, PA, January 2022

On this last snow boot adventure, the seed-heads of memorable note were the quintessential wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa) pom-pom tufts, a scratch-n-sniff plant even in the depths of winter, hinting to soft oregano or earl grey tea. Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) graces the meadow at its entry. Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) with evident signs of birds feasting on its sea-urchin seed-heads.

Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

All classic natives to incorporate into the land you are rewilding and stewarding, yet be warned that wild bergamot and common milkweed both need vast space to roam, given their high sociability level. Just like humans, plants are social organisms that interact with their neighboring plant kin or as defined by Encyclopedia.com, plant sociability is “a measure of the distribution pattern and organization of a species” (2018).

In my study with Claudia West, world renowned landscape designer with Phyto Studio, we practiced categorizing the sociability of common native landscaping plants into 5 levels, based on the Braun-Blanquet System.

Level 1: Isolated individual plants

Level 2: Occasionally present, less than 20% of observed landscape

Level 3: Small groups present, 20-40% of observed landscape

Level 4: More frequent patches, 40-60% of observed landscape

Level 5: Larger populations of higher density, 60-80% of observed landscape

In observation of the species seeded in this multi-acre meadow, there are level 5 grass species like Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans), an “aggressive” grower that spreads via rhizomes. So, the highlighted flowering forbs that remain in this meadow are higher level on the sociability scale, simply because they are even present in a plant community of highly dispersive grass species, in a mature meadow such as this one.

Broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus) along the meadow trail | Kellys Run, Holtwood, PA, January 2022

Another example of a more broad spreading native grass species that happens to also have stellar winter interest is broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus).

Quick Quiz: From observing the image above, how would you classify the sociability of this grass meadow species? Do you observe a single specimen or over 50% present in this meadow?

Translating this to when ecological gardeners design their lawn conversion project, requires some time learning plants and how they interact with others. This does mean there will be a steep learning curve on your first plantings when you foolishly plant wild bergamot in a small space (less than 500 sq ft.) and expect it to mingle well with others. If creating a highly diverse landscape is your aim, choose native plants with lower sociability (take it from me, lesson learned on schoolyard habitat #1 :)). Also, embrace your clay soil, it helps to keep some of those higher level rhizomatic species a bit more at bay.

Eastern white pine grove (Pinus strobus)

Eastern white pine cone (Pinus strobus)

In the next layer of your ecosystem stroll, trees can be observed for their stunning winter interest at Clark Nature Preserve. A grove of Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) appears to be intentionally planted along the edge of the meadow, as part of the Lancaster Conservancy’s effort with the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS) Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) to plant more native trees on the preserve.

A wonderful addition to add to your next lawn conversion project, if you have the space for this native evergreen at a mature height of 80’ and width of 40’. You’ll be full of gratitude in winter with its vivid green pop, fresh aromatics, and possibly an uplifting #homegrown #homebrew tea (if you don’t have pine allergies!).

Chinese mantid (Tenodera sinensis) egg case | Clark Nature Preserve in Pequea, PA, January 2022

An occasional pine cone is spotted and dozens of Chinese mantid (Tenodera sinensis) egg cases tucked into the needles. A reminder to first correctly ID, remove, then feed these cases to wild birds at your feeder station or local wild bird rehabilitation, or even treat your chickens or pet tarantula (!).

Allowing the egg cases to populate into hundreds of baby mantises will introduce an unbalanced number of apex predators into your landscape, greatly diminishing the amount of bees and butterflies on your property. These large praying mantis species eat bees and butterflies like a hungry teenager ravishingly eating a bowl chips. There is no shame, folks, its brutal to witness, especially when observed in your own labor-of-love #homegrownhabitat.

House Rock overlook | Clark Nature Preserve in Pequea, PA, January 2022

Sweet birch (Betula lenta)

Female seed structures

Female (left) and male (right)

A final winter interest inspiration was found on the House Rock outcropping, overlooking the stunning Susquehanna River. Lined up in a row, with the best views of the river, sat the upright female Sweet birch (Betula lenta) cone-like structures. When viewed up close, they look like baby pinecones and from a distance, delicate tree decorations. The sweetness of a nibbled twig end conjures up memories of rootbeer barrel candies and birchbeer soda, enjoyed from the Amish-owned corner grocer, as a kid visiting my “Oma -n- Opa” in Leola :).

Carex and ice crystals on House Rock overlook | Clark Nature Preserve, Pequea, PA, January 2022

Just as I thought I’d gathered all the winter interest inspirations from this adventure, the sight of this cool season sedge (Carex spp.) was tucked under a rock ledge with artful ice crystals catching the winter sun, casted over the river. Sedges are a must for an ecological garden, crucial as a living/green mulch and host to skipper butterflies. Given that they grow in the cooler seasons, they help tremendously in dampening the impact of winter weeds. A perfect pause to close this winter interest and sociability observation adventure, just enough to satisfy this Waxwing wandering :).

by Elyse Jurgen | Waxwing EcoWorks Owner/Founder

Are you also an ecological gardener on the prowl for a botanically rich observation adventure? Share your winter interest and plant sociability comments below and give this post some love. Thank you!

Ferns and Fungi | Using iNaturalist as an Observation Tool

To beat this Summer’s heat, between the buzz of new consultations, designing front lawn conversions, or hammering out the logistics of the latest schoolyard habitat planting, I found myself daily desiring to deeply sink my feet into a loamy woodsy path, wade in a cooling stream, or wait until the cooler (sounds like an overstatement) evening hours to explore fallow fields for wildflowers. Simply finding a trail and being amidst ferns, later Summer forming fungi, and flora rejuvenates the soul, with the added benefit of inspiring new designed plant communities.

Northern Maidenhair Fern (Adiantum pedatum) | Kelly’s Run Nature Preserve, Holtwood, PA

Often I feel compelled to explore, unstructured, but have found that my “always need to be productively saving the planet” mindset, creeps into my play time, hankering for a bit more purpose in this Summer’s daily woods frolic. Recording my observations on iNaturalist has been a tactful bridge for me to “free two birds with one hand”; enjoying the tranquility of a Lancaster Conservancy wild brook trout stream AND capturing all the biodiversity I witness along the stream’s banks. This citizen science app, crafted by UC Berkley Master’s students in 2008, is a useful tool to assist in the much needed slowing down in our hurried society and the intentional practice of learning new species in a place (yet another skill once lost and needing to be nurtured in our society).

Ferns and fungus (among a whole host of flora) have always been tricky for me to identify, but this citizen science tool has been empowering to hone the skill of paying attention to details and ultimately making identifications. With iNaturalist, you are not alone (this is starting to sound like an infomercial, I promise I don’t make a commission), in fact a whole community of collaborators may assist you in your rewilding adventures. How cool is that? With the aid of local botanists, mycologists, and entomologists, your mini mushroom mystery is solved graciously by @jody41 or your starry campion (Silene stellata) speculation is confirmed by @jrambler.

Orange pinwheels (Marasmius siccus) | Kelly’s Run Nature Preserve, Holtwood, PA

In more regular use of iNaturalist, I have discovered that the pink little tags that show up on your observations is another iNaturalist user; (1) confirming your identification (a great self-confidence booster), (2) suggesting another identification with “keying” pointers, or (3) the ultimate favorite a series of members in a back and forth botanizing debacle on the correct identification of the species.

As in this picture shown below of (spoiler alert!)… Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), @jrambler and @mjpapay were determining if this fairly tiny specimen that was fooling me to think it was a spleenwort was actually a very young Christmas fern. Gloss over this next part if you aren’t into nerding out on plants….… yet ;). The confirmed Christmas fern ID from @mjpapay stated, “the auricle/ear is also present on leaflets of ebony Spleenwort and other ferns as well. However, your excellent photo shows leaflet details that Polystichum acrostichoides has from very early on (when tiny) and right through to full-size. The edges of the leaflets are serrated, and each serration ends in a stipule (an elongated thin point)”. Thank you, thank you @mppapay it is a very excellent photo, I mean, yes, the auricle is present as is the serration on the stipule ends, leading us to believe this is in fact of Christmas fern. End of botanizing tale.

Baby Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) | Kelly’s Run Nature Preserve, Holtwood, PA

The joy of reading through their reasoning was like having a private (and free!) botanist on your woodsy frolic. Well, to be fair not during, unless you have epic reception and like to stare out your phone when in the woods. Not I! I upload my photos after dark on the comfort of my couch, and realistically wait a few days until a fellow iNaturalist buddy can help out on the species that leave me stumped. In this way you can balance your need for no screen time when out on an adventure and only use your smartphone or digital camera to meditatively take pictures.

Nothing to lose, only everything to gain, eh? Hone your skill of knowing the plants around you and make a game of going to the woods with your friends and family (totally cooler than Pokemon GO). Or simply use it to inventory the biodiversity on your own property (like a mini bioblitz)- a service now offered to Waxwing management customers (super excited about this!). Get started here or simply upload the free app!

Are you also an iNaturalist observer? Please give the post a like and share your iNaturalist adventures in the comments below!

Price Elementary Schoolyard Habitat, Design and Build | Phase I

This October, the Schoolyard Habitat Residency student cohort at Price Elementary in Lancaster city completed the first phase of the design and build of a brand new outdoor living laboratory for cross-curricular education and wildlife conservation! It was a joy to facilitate Ms. Honeywell’s former 4th grade class through the continuation of their schoolyard habitat design and build project, by planting the living foundation of the space with 21 ecologically beneficial shrubs and trees. This step sets the stage for the upcoming Spring 2021 student cohort to install the herbaceous layer of the designed woodland edge urban ecosystem.

In preparation for this planting, the 4th grade student class engaged in close observation of their schoolyard and its surroundings through the winter months of 2019-2020; observing signs of wildlife and any shortcomings of this urban habitat in meeting the needs of their adopted critters (ex: red back salamander, Monarch butterfly, Red-bellied woodpecker, beneficial beetles, etc.). Selecting a silent sit-spot was integral to making these observations and to offer recommendations for the new habitat they were challenged to collaboratively design and build. As an opportunity for whole school engagement, Carol Welsh and I guided teachers and students (PreK-5th) in a nature journaling watercolor process; an accessible activity for all to engage and gain comfort to utilize the outdoors as a space for learning.

In Fall 2020, after a hiatus in the project, due to the pandemic, Bianca Cordova, Community School Director, generously and joyously gathered small student groups to continue the Schoolyard Habitat Residency with the culminating stages of designing and beginning to build the 4 elements of a habitat into their underutilized schoolyard lawn space.